Nigel Brown: Last the Distance

-

Nigel BrownAh Yes Life, 1984Acrylic on board83 x 118 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownAh Yes Life, 1984Acrylic on board83 x 118 cm (unframed)

87 x 123 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownBeyond Laingholm, 1985Oil on hardboard88 x 120 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownBeyond Laingholm, 1985Oil on hardboard88 x 120 cm (unframed)

93 x 125 cm (framed) -

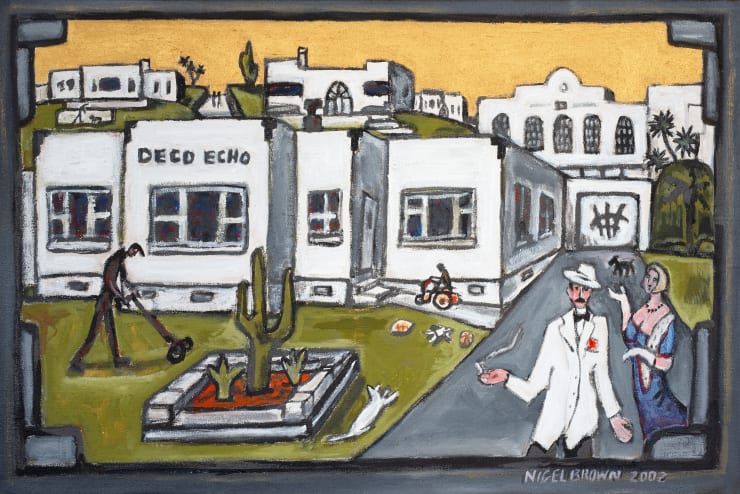

Nigel BrownDeco Echo, 2002Acrylic on linen59 x 89 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownDeco Echo, 2002Acrylic on linen59 x 89 cm (unframed)

73 x 125 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownThe Ghost of a Chance We Will Discover Anything, 2008Acrylic on board80 x 180 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownThe Ghost of a Chance We Will Discover Anything, 2008Acrylic on board80 x 180 cm (unframed)

83 x 184 cm (framed) -

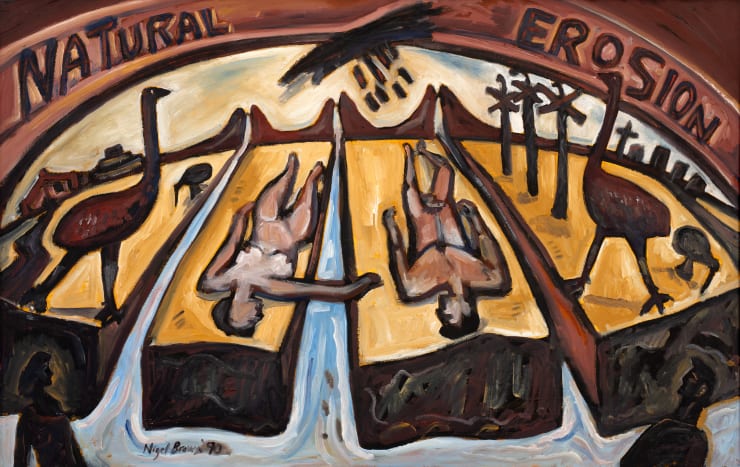

Nigel BrownNatural Erosion, 1990Oil on hardboard70 x 110 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownNatural Erosion, 1990Oil on hardboard70 x 110 cm (unframed)

75 x 115 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownMarae in the City, 1988Oil on hardboard79 x 117 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownMarae in the City, 1988Oil on hardboard79 x 117 cm (unframed)

84 x 122 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownBeware of Magpies Tolaga Bay PTG, 1991Oil on board60 x 80 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownBeware of Magpies Tolaga Bay PTG, 1991Oil on board60 x 80 cm (unframed)

63 x 83 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownThe Goal, 1982Oil on board73 x 54 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownThe Goal, 1982Oil on board73 x 54 cm (unframed)

77 x 58 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownStrangers and Journeys, 2024Acrylic on ply cut-out96 x 66 cm

Nigel BrownStrangers and Journeys, 2024Acrylic on ply cut-out96 x 66 cm -

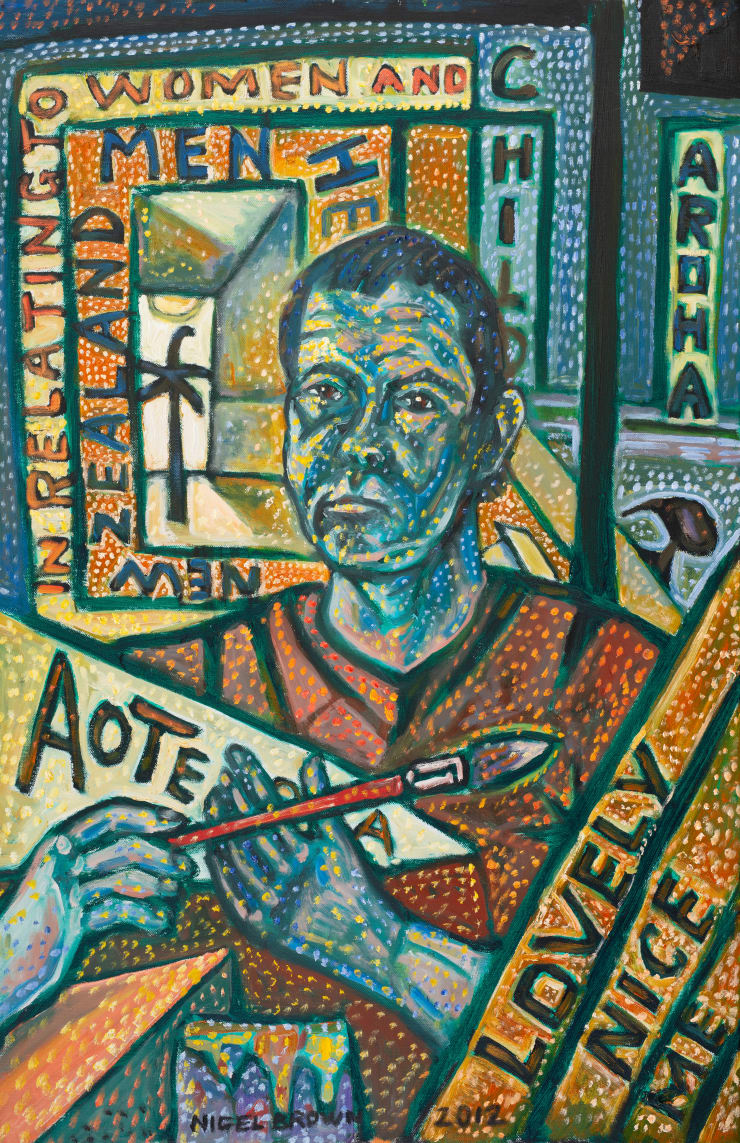

Nigel BrownLovely Nice Self, 2012Oil on canvas90 x 60 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownLovely Nice Self, 2012Oil on canvas90 x 60 cm (unframed)

93 x 63 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownLegend for the West, 1986Acrylic on hardboard60 x 120 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownLegend for the West, 1986Acrylic on hardboard60 x 120 cm (unframed)

64 x 124 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownScott’s Hut Cape Evans, 1999Oil on canvas75 x 136 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownScott’s Hut Cape Evans, 1999Oil on canvas75 x 136 cm (unframed)

81 x 142 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownOne Tree Hill Across the Manukau Orange Version 1973, 1973Acrylic on hardboard80 x 120 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownOne Tree Hill Across the Manukau Orange Version 1973, 1973Acrylic on hardboard80 x 120 cm (unframed)

86 x 127 cm (framed) -

Nigel Brown2 Cars, 1980Acrylic on board60 x 42 cm (unframed)

Nigel Brown2 Cars, 1980Acrylic on board60 x 42 cm (unframed)

64 x 46 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownBehind the Easel, 1982Oil on board51 x 24 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownBehind the Easel, 1982Oil on board51 x 24 cm (unframed)

56 x 29 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownVan Gogh Variation, 1985Oil on board29.5 x 29 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownVan Gogh Variation, 1985Oil on board29.5 x 29 cm (unframed)

34 x 33.5 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownNature Nature Me Too, 2018Acrylic on canvas40.5 x 60.5 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownNature Nature Me Too, 2018Acrylic on canvas40.5 x 60.5 cm (unframed)

43.5 x 64.5 cm (framed) -

Nigel BrownCook as Integrity Surrounded by Bastards, 2014Oil on linen80 x 60 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownCook as Integrity Surrounded by Bastards, 2014Oil on linen80 x 60 cm (unframed)

85 x 65 cm (framed) -

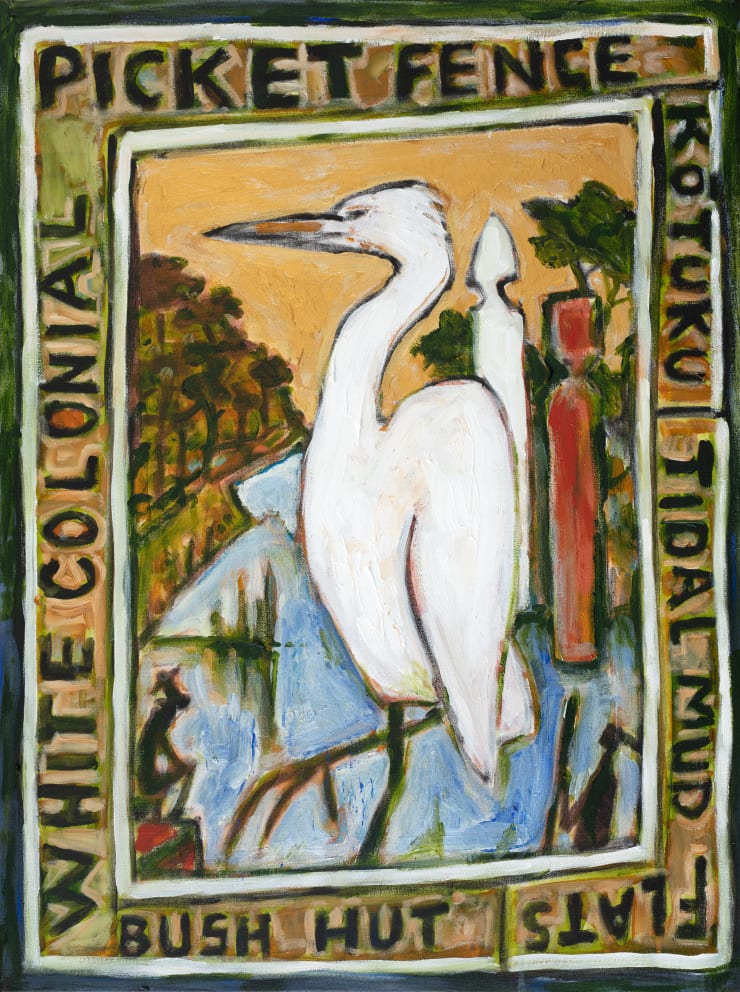

Nigel BrownWhite Colonial White Kōtuku, 2024Acrylic & glitter on canvas80 x 60 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownWhite Colonial White Kōtuku, 2024Acrylic & glitter on canvas80 x 60 cm (unframed)

83 x 63 cm (framed) -

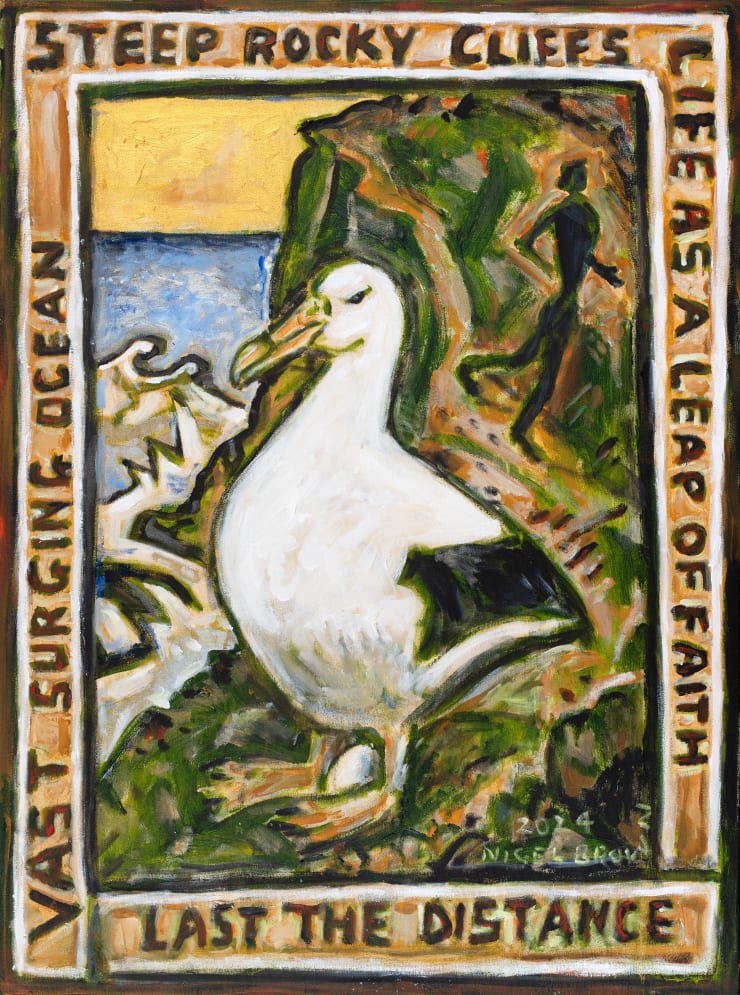

Nigel BrownLast the Distance, 2024Acrylic on canvas80 x 60 cm (unframed)

Nigel BrownLast the Distance, 2024Acrylic on canvas80 x 60 cm (unframed)

83 x 63 cm (framed)

The title of this exhibition – suggestive of being in for the long haul is taken from that of a 2024 painting of an albatross. The bird has appeared in various guises throughout Nigel Brown’s career and was the subject of his 2015 exhibition ‘Albatross Neck’, at Artis Gallery, on the theme of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. In this recent painting, the magnificent bird surveys the vastness of the Southern Ocean from its rocky perch, and its serenity at rest is in stark contrast to the dark background figure of a running woman.

The earliest work in this survey is a subject Brown has made his own One Tree Hill Across the Manukau (1973) was painted two years after he graduated from the Elam School of Fine Arts, and included in his second one-person exhibition at Moller’s Gallery in Queen Street. The massive obelisk, funded by John Logan Campbell as a memorial to the Māori race, stands sentinel against an ominously hot and copper sky. To its left is the lone Monterey pine, removed in 2000 after being attacked by Māori activist Mike Smith. The obelisk and tree also appear here in Beyond Laingholm (1985), a view across the Manukau Harbour from where Brown was living at the time, while a dead stump testifies to the settlers’ brutal assault on the landscape. A similar theme occurs in Natural Erosion (1990), from a series prompted by reports of the depletion of the ozone layer, in which the gradual wearing down of a range of mountains is witnessed by a pair of giant and now extinct moa.

Spanning the distance, this collection of 20 works illustrates the highly distinctive range of iconography that Brown has developed and deployed during the last half century. His essential concern is the human condition, as in the relationships between individuals and with their natural environment. One such issue, which convulsed the nation in 1981, was the Springbok Tour, represented here by The Goal (1982), in which a skull-headed rugby player scores what is presumably an own goal beneath the posts. In the same year, and now living in his studio in Karaka Street, Newton, Brown produced Behind the Easel (1982), seating himself deep in thought behind an unseen painting. The weather-beaten Karaka Street studio also appears in Legend of the West (1986), inspired by the artist’s childhood memories of Western films. A pair of gun-slingers are surrounded, cinematically, by a cavalcade of images reflecting Brown’s concerns, among them the feminist and anti-nuclear movements.

Ah Yes Life (1984) was one of the large number of anti-nuclear works painted during Brown’s involvement with the establishment in Auckland of VAANA – Visual Artists Against Nuclear Arms. At its centre is humanity’s salvation, a symbolic ark, which first appeared in the artist’s Arama series in the 1970s, derived from the formal simplicity of the houses in Arama Avenue viewed across the valley from his own home in South Titirangi, while the austerity of the composition was an acknowledgment of the influence of Colin McCahon, one of his teachers at Elam.

Just as Coleridge’s epic poem of 1798 may have been inspired by the exploits of James Cook, Brown has explored the latter’s increasingly precarious place in our own history. The previously unexhibited triptych, The Ghost of a Chance We Will Discover Anything (2007-08), presents a bewildered Cook flanked by a man with a spade and a woman with a broom, and his progress illuminated by McCahon’s lamp and assertive ‘I AM’. Over time Brown has treated the navigator as both a positive and negative force, and in Cook as Integrity Surrounded by Bastards (2014) he is assailed from all sides, the responses to his legacy even extending to a whakapohone, the baring of buttocks.

A consequence of Cook’s visit to Aotearoa was the onset of settlement from Europe, as alluded to in White Colonial White Kotuku (2024). The white heron, selected as the symbol for New Zealand’s Sequicentennial year 1990, appears alongside a carved pou whenua and tidal mudflats, and is contrasted with a white picket fence and a bush hut. The challenges of biculturalism are also referred to in Marae in the City (1988), in which the titular subject is elevated on a podium, suggestive of a sanctuary and cultural support, while a black-singleted male nurturing a young child is surrounded by motorways and high- rise buildings – and a distant One Tree Hill.

Brown’s career has been further distinguished by his working in thematic series, which he estimates now number well over a hundred. Among the wide-ranging subjects also represented in this exhibition are Antarctica (which he visited as part of the inaugural Artists in Antarctica programme in 1997-8), while his personal influences include Expressionism and the challenges of working in such media as stained glass and woodcut.

The most recent work in this collection is a plywood cut-out, Strangers and Journeys (2023-25), its title referencing the 1972 novel by Maurice Shadbolt, who was a near neighbour of Brown’s in South Titirangi. The subject is another black-singleted New Zealand male, an archetype who first emerged in the artist’s work in the 1970s. A muscular pioneer, his head is bowed as if resigned to the weight of history, or perhaps its expectations. Half a century on, and in regard to this particular painting, Brown admits there is more work to be done, noting: ‘… we are all strangers to each other in varying degrees and we are all on journeys.’

Richard Wolfe, April 2025